Festival d'Aix-en-Provence, 20/07/2022

Rossini : Moïse et Pharaon

Chœur de l'Opéra de Lyon

Orchestre de l'Opéra de Lyon

Michele Mariotti

Rossini's original thoughts on the subject of Moses and the Book of Exodus reached the stage in Naples in 1818. Eight years later, receiving a commission from Paris Opera, but without enough time to write a wholly original work - that would eventually be Guillaume Tell, in 1829 - Rossini did what he had done so often before, and looked to his back catalogue to see if there was anything useful there that could be adapted to French tastes. So Moïse et Pharaon was born, adapted from Mosè in Egitto, with the addition of an extra act, of a ballet (mandatory at the Paris Opera), and a host of other amendments, so many that it truly is a separate work, and not a mere translation. It also became one of the first examples of what was to become a distinct operatic model, the French grand opéra. There's an act missing for complete compliance, but everything else was there, the epic subject, the pageantry, scenic magic, the significant choral scenes, and the ballet.

Packing what is meant to be a grandiose spectacle onto the compact stage of the Archevêché was always going to take real ingenuity, and Tobias Krantzer certainly displayed that. He played the 'refugees versus vested interests' card, most visibly in the first act, where the stage was split between a refugee camp for the Hebrews, and a corporate headquarters for the Egyptians. With one significant exception, dress was modern, executive suits for the Egyptians, rag-tag assemblies of mis-matched clothing for the Hebrews. The one exception was Moses himself, who could have walked straight out of De Mille's The Ten Commandments. Michele Pertusi doesn't quite look like Charlton Heston, but there wasn't much in it.

This immediately posed the issue of whether he was an actual person - even though he has family here, a sister, her husband and her daughter - or rather a powerful symbol. The Plagues are less explicitly defined in Rossini's opera. The three days of darkness here became the Egyptians going blind; the water-to-blood, hail- and fire-storms, locusts and pestilence are all mentioned in one panicked intervention in Act 3, and Krantzer presents them as ecological disasters, with news reports flashing up on giant screens. Finally, the first-born deaths do not happen at all here (where they did in Mosè in Egitto). As for the promised land, as the Hebrew chorus solemnly intones the final Cantique, the stage lights come up on a beachside resort, holiday-makers lounging around on recliners, sipping cocktails or eating ice creams, playing beach games and generally taking in the sun - not a very likely outcome for refugees, or at least not for a very long time. Again, an issue of fantasy versus reality.

However, in many respects the driving force of the drama reduces the clash of races down to an impossible romance between Anaï, niece of Moses, and Aménophis, Pharaoh's son and heir, and much of what happens - Pharaoh's repeated breaking of his promise (or contract, here) - emerges from this, because Aménophis cannot and will not accept the departure of Anaï. To be honest, Aménophis comes across like a spoiled toddler, throwing one strop after another. I had very little sympathy for him and, in consequence, not much for Anaï either because I couldn't see what she saw in him in the first place. Krantzer's not to blame for that, he worked with what he was given, and Rossini's original Egyptian prince in the 1818 version was not, as far as I recall, such a brat.

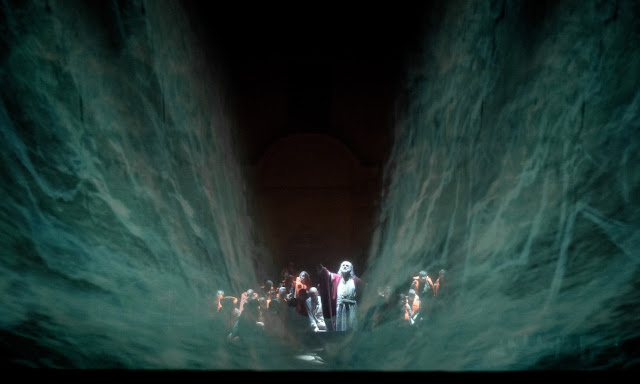

The parting of the Red Sea was, inevitably, a video effect, passably successful for the crossing, while for the Egyptians' attempt, it was an actual film, a group of executives running over sand, and then the water coming up around them and them drowning. The drowning wasn't so funny but I have to say the first part of the film looked like some sort of cock-eyed advertisement. I'm pretty sure I've seen something like that in an advert some time. On the whole, the production was good, if a little superficial, but the whole grand opéra genre is very difficult to pull off these days, and this was an honourable attempt.

|

| The crossing of the Red Sea. Michele Pertusi as Moses (centre) Moïse et Pharaon, Festival d'Aix-en-Provence (© Monika Rittershaus, July 2022) |

Like most works in this style, it's quite a long piece, and it's to Michele Mariotti's considerable credit that it never flagged. Chorus and Orchestra of the Lyon Opera were in fine form, and this was the last night, so some fatigue might have been expected, especially in this heat, but there was none to be detected. Pertusi has been singing Moses (in both versions) for a good 25 years, and if he's not quite as sonorous a bass as might be desired, the authority is almost tangible. Jeanine De Bique and Pene Pati were the lovers. De Bique had a little trouble with the lowest part of the role, and became a little inaudible there, particularly in ensembles with chorus, but as the voice rises she became much clearer, and the ornamentation came effortlessly. Pati looks like a rugbyman strayed from his pitch, which is not surprising, because that's pretty much what he was, apparently, and the voice is good, well-centred generally. He's not completely comfortable with Rossinian decoration - even though, in writing for the Paris Opera, Rossini tended to tone it down, because the French vocal school wasn't based in the belcanto vocal techniques - but he gave himself over to the part - tantrums and all - with conviction.

Adrian Sâmpetrean was a sound Pharaoh - despite being a title role, he doesn't really have that much to do on his own, but is an essential part of ensembles - and Mert Süngü made a strong impression as Eliézer, Moses' brother, a little lightweight in the ensembles, but a clear, sharp tenor timbre used to good effect in the long Act 1 narrative of his negotiations with Pharaoh. However, of the secondary roles, it was Vasilisa Berzhanskaya who ran off with the honours as Sinaïde, Pharaoh's Queen who pleads in favour of the Hebrews. She has a dazzling aria in Act 2, begging her son to renounce his hopeless attachment to Anaï, and brought a lustrous, bright mezzo voice and an infallible technique to it to sensational effect. Another one for the watch list.

[Next : 21st July]