Opera North, 02/11/2019

Martinu : The Greek Passion

Chorus and Orchestra of Opera North

Garry Walker

The Greek Passion is Martinu's last opera, but it exists in two distinct forms. Originally completed in 1957 for performance at the Royal Opera House in London, this production fell through, and Martinu offered it to one of the other houses which had expressed an interest in his latest operatic project. However, both his publishers, and the director of the Zurich Opera, where it was to go, wanted revisions. Martinu complied, to a much greater extent than could have been anticipated, producing a work very substantially different to his original version. It's the Zurich version that I know, through the Mackerras/Supraphon recording, but I clearly wasn't reading the right magazines at the time, because I was completely unaware of the London version being successfully pieced together for performance at Bregenz in 1999. Apparently, it is becoming usual to favour the London version in current performances, not that there are very many of those in the first place.

There is only one significant change to the actual story, and that is at the very end, which is more despairing than the Zurich version. The rest of the libretto, derived from Nikos Kazantsakis's Christ Recrucified, and written, in English, by the composer with the author's approval, is more or less the same. In a Greek village, Lycovrissi, under Ottoman rule, the Elders begin the preparations for the following year's Passion Play by selecting the villagers who are to play the principal roles. Their complacent lives are interrupted by the arrival of a group of refugees from another village which has been sacked by the Turks, who seek to put down new roots in order to thrive once more. The Lycovrissi priest rejects them, pretexting (falsely) cholera as his reason, but the some of the 'chosen' villagers - Katarina, who is to be the Magdalen, and the shepherd Manolios, who is to play Jesus Christ - argue for compassion, and advise the newcomers to settle on the nearby Sarakina mountain. In the months that follow, Manolios identifies more and more closely with his role, with the example of the struggling refugees before him, until the Lycovrissi Elders become alarmed by his growing sway over the villagers, and first excommunicate Manolios, then effectively authorise Panait - playing Judas - to murder the shepherd. In the Zurich version, the Sarakina settlers, unable to sustain themselves on the bare mountain slopes without assistance from Lycovrissi, abandon the site and move on, taking Manolios's body with them in solemn reverence. In the London version, the implication is strong that they all die, of starvation and exposure.

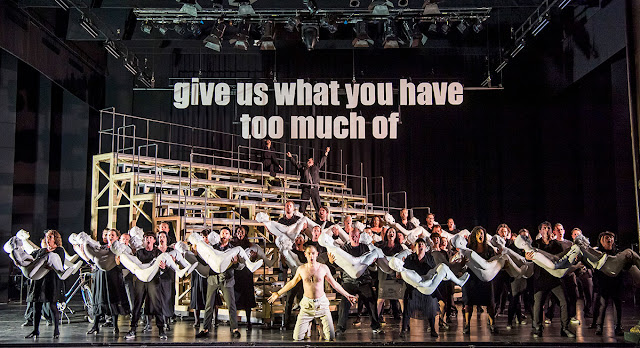

The resonances of this plot to present-day circumstances are all too obvious. It is not just the question of taking in refugees, it is also a reflection on the homeless in our society, for these are not refugees in the current sense of those fleeing wars or oppressive regimes in the Middle East, Africa or South America. The newcomers are members of the same society, of the same nation, the difference being that Lycovrissi has come to an accommodation with its Turkish overlords, whereas one may assume that wherever the newcomers came from, there was resistance that was met with a crushing response. The message "Give us what you have too much of" literally hangs over the proceedings in this production, and Martinu's concern with man's (in)humanity towards man is all too clear.

It's quite an odd thing, coming to an opera that, ostensibly, is somewhat familiar, and finding something very different. The London version is more abrupt, with more speech, and a narrator, while the Zurich one is more through-composed and lyrical. There are some moments that have remained more or less the same, notably much of Act 3 - Manolios's dream, and the second scene with Katarina in particular - but it's more of an ensemble piece than the later version, with less individual solo singing. I have to say I prefer the second version, the voices have more of a chance to shine, and two scenes are, I think, better structured; the conclusion of the second act, the laying of the foundations on Sarakina, and the final scene, which is more moving. That doesn't prevent the London version from packing a serious punch, though.

Christopher Alden has updated the action somewhat, though you still get the impression of a remote territory. There are no digital references, characters smoke, costume is somewhat vague - if you had to pin it down, I would hazard a guess at the 70s, perhaps - but there is some updating of the text. Yannakos has a bike rather than a donkey, there's talk of lager and crisps, and an inserted reference to 'bloody vegans', which got a good laugh from the audience. The refugees are represented by white, seated mannequins, not quite faceless, but anonymous, and manipulated with greater or lesser care by all and sundry. The set is sparse, a large set of wooden bleachers to house the chorus, and suggestive of the stark slopes of Sarakina, a few tables and chairs.

Katarina looks vaguely like Bettie Page, while Lenio (Lorna James), Manolios's fiancée, looks like a young Billie Piper. The male principals are more neutral, though Panait is a stereotypical biker, complete with forehead tattoo, to make the point he's a bad-boy type, and Manolios has the Christ-like long hair. Alden's direction was mostly unobtrusive, with a couple of ideas I liked. Panait's constant presence whenever Katarina is on scene - at the start of the opera, they are lovers - was a good touch. On the other hand, I thought his view of Priest Fotis (leading the refugee group) was too zealous, and lacked poise.

Martinu, like Janáček before him, did not write operas whose arias you can walk out humming. You can walk out with a theme stuck in your head, but you will have heard it in the orchestra, rather than in the voices. The vocal cast here was strong, Nicky Spence a clear but restrained Manolios, Paul Nilon bright and eager as the naive Yannakos, Magdalena Molendowska a warm-voiced Katarina, amongst others, and the chorus was excellent, which is a vital element of the whole. However, it's the orchestra that carries much of the emotional weight of the work, Martinu's radiant, rhapsodic orchestral music the true vehicle of expression, and Garry Walker and the Orchestra of Opera North gave full value to this aspect of the score.

[Next : 3rd November]

Chorus and Orchestra of Opera North

Garry Walker

The Greek Passion is Martinu's last opera, but it exists in two distinct forms. Originally completed in 1957 for performance at the Royal Opera House in London, this production fell through, and Martinu offered it to one of the other houses which had expressed an interest in his latest operatic project. However, both his publishers, and the director of the Zurich Opera, where it was to go, wanted revisions. Martinu complied, to a much greater extent than could have been anticipated, producing a work very substantially different to his original version. It's the Zurich version that I know, through the Mackerras/Supraphon recording, but I clearly wasn't reading the right magazines at the time, because I was completely unaware of the London version being successfully pieced together for performance at Bregenz in 1999. Apparently, it is becoming usual to favour the London version in current performances, not that there are very many of those in the first place.

There is only one significant change to the actual story, and that is at the very end, which is more despairing than the Zurich version. The rest of the libretto, derived from Nikos Kazantsakis's Christ Recrucified, and written, in English, by the composer with the author's approval, is more or less the same. In a Greek village, Lycovrissi, under Ottoman rule, the Elders begin the preparations for the following year's Passion Play by selecting the villagers who are to play the principal roles. Their complacent lives are interrupted by the arrival of a group of refugees from another village which has been sacked by the Turks, who seek to put down new roots in order to thrive once more. The Lycovrissi priest rejects them, pretexting (falsely) cholera as his reason, but the some of the 'chosen' villagers - Katarina, who is to be the Magdalen, and the shepherd Manolios, who is to play Jesus Christ - argue for compassion, and advise the newcomers to settle on the nearby Sarakina mountain. In the months that follow, Manolios identifies more and more closely with his role, with the example of the struggling refugees before him, until the Lycovrissi Elders become alarmed by his growing sway over the villagers, and first excommunicate Manolios, then effectively authorise Panait - playing Judas - to murder the shepherd. In the Zurich version, the Sarakina settlers, unable to sustain themselves on the bare mountain slopes without assistance from Lycovrissi, abandon the site and move on, taking Manolios's body with them in solemn reverence. In the London version, the implication is strong that they all die, of starvation and exposure.

The resonances of this plot to present-day circumstances are all too obvious. It is not just the question of taking in refugees, it is also a reflection on the homeless in our society, for these are not refugees in the current sense of those fleeing wars or oppressive regimes in the Middle East, Africa or South America. The newcomers are members of the same society, of the same nation, the difference being that Lycovrissi has come to an accommodation with its Turkish overlords, whereas one may assume that wherever the newcomers came from, there was resistance that was met with a crushing response. The message "Give us what you have too much of" literally hangs over the proceedings in this production, and Martinu's concern with man's (in)humanity towards man is all too clear.

|

| John Savournin as Priest Fotis (front) and Paul Nilon as Yannakos (back) with the Chorus of Opera North The Greek Passion (© Tristram Kenton for Opera North, 2019) |

Christopher Alden has updated the action somewhat, though you still get the impression of a remote territory. There are no digital references, characters smoke, costume is somewhat vague - if you had to pin it down, I would hazard a guess at the 70s, perhaps - but there is some updating of the text. Yannakos has a bike rather than a donkey, there's talk of lager and crisps, and an inserted reference to 'bloody vegans', which got a good laugh from the audience. The refugees are represented by white, seated mannequins, not quite faceless, but anonymous, and manipulated with greater or lesser care by all and sundry. The set is sparse, a large set of wooden bleachers to house the chorus, and suggestive of the stark slopes of Sarakina, a few tables and chairs.

Katarina looks vaguely like Bettie Page, while Lenio (Lorna James), Manolios's fiancée, looks like a young Billie Piper. The male principals are more neutral, though Panait is a stereotypical biker, complete with forehead tattoo, to make the point he's a bad-boy type, and Manolios has the Christ-like long hair. Alden's direction was mostly unobtrusive, with a couple of ideas I liked. Panait's constant presence whenever Katarina is on scene - at the start of the opera, they are lovers - was a good touch. On the other hand, I thought his view of Priest Fotis (leading the refugee group) was too zealous, and lacked poise.

Martinu, like Janáček before him, did not write operas whose arias you can walk out humming. You can walk out with a theme stuck in your head, but you will have heard it in the orchestra, rather than in the voices. The vocal cast here was strong, Nicky Spence a clear but restrained Manolios, Paul Nilon bright and eager as the naive Yannakos, Magdalena Molendowska a warm-voiced Katarina, amongst others, and the chorus was excellent, which is a vital element of the whole. However, it's the orchestra that carries much of the emotional weight of the work, Martinu's radiant, rhapsodic orchestral music the true vehicle of expression, and Garry Walker and the Orchestra of Opera North gave full value to this aspect of the score.

[Next : 3rd November]